If you are interested in exhibiting any of these films, please contact us for assistance at jimjennings906@gmail.com.

In Alphabetical order:

A Fairy Tale (1981-1983, b/w, 16mm, silent, 8 min.)

In collaboration with Chris Piazza.

The physical effect of Jennings’ use of spatial and rhythmic tension coupled with visual surprises serves to uncover the unsuspected profundity of small things. -San Francisco Cinematheque, 1984

Set in St. Augustine, Florida, “A Fairy Tale” is a masterpiece of geometry and rhythm, as lines and shapes are set to, and create, a silent percussion.”–Karen Treanor

Bike Study (2002, b/w, 16mm 7 min.)

Bike study honors a simpler, communal way of life, in which individuals are content to have peers rather than subordinates. Shot in Netherlands, this film presents an ideal – democracy – in the concrete form of a bicycle park.– Karen Treanor

Brighton (1983, color, silent, 16mm, 7 min., 18 fps)

By composing “sets” in which “actors” perform, the everyday becomes fictional.

– Karen Treanor, Notes to “Eight Films by Jim Jennings” at Millennium Film Workshop, December 19, 1998

Bruges (2006, b/w, 16mm, silent, 6 min.)

“Bruges” depicts life in a hotel room in a quaint, Belgian tourist town. Residents are also depicted walking and cycling to work on one of the city’s many canal bridges, as wildlife experiences its own reality in the waters below. A fine example of Jennings’ skillful editing.

– Karen Treanor

Bye Bye Bob (1990, b/w,16mm, sound, 10 min.)

The morning commute across the bridge becomes a requiem which ends as the procession goes underground. In memory of Bob Fleischner. (Soundtrack from “Enchanted” by George Shearing and the Montgomery Brothers.)

– Karen Treanor, quoted in the catalogue of the 43rd San Francisco International Film Festival.

Canal Cinema (1983, color, 16mm, silent, 18 fps, 8 min.)

“Canal Cinema” relates the “magical moments” in which everyday sights become living art. Filmed in New York City’s Chinatown, this film presents the interplay between common street scenes and aesthetic visions.

– Karen Treanor

Chambers (1978, b/w, 16mm, silent, 6 min.)

“‘Chambers begins by camera flaring to a spiral camera movement, on foot and gently circling, looking up (as at the heavens–only this is indoors, one would think). Variably shuttered darks then come and go to lightest whites, to pans of further walls and ceiling spaces of this chamber (a castle a la 1920s architecture done to mime a Roman square). The camera passes frame-like, repetitious wall tiles of this citified abode, then comes to rest quite briefly while it stations for a moment in the dark, then to metamorphose to an altogether different shot depicting shape of arch against daylight. A breathing pause ensues, and then the camera travels up again to contemplate with unaffected wonder the ceilings of (the heavens of) this house. In ‘Chambers’ too there is a parallel that serves as echo to the play of our diurnal sense of time: redoubled streamings of light to dark, besides the normative exposures in between, map fertile counterparts to what the domes and arches pictured in the film were originally built to mime–that is, the skies.

‘Chambers’ provides us with specific details of the mundane local place in which it has been filmed, yet never ceases to communicate its satisfying finds, and though the film reiterates its simple, numbered gestures, somehow this never tires. Jennings’ camera feeds the eye and then the spirit, never pausing to ‘inform.’ There is a sense of play here and unselfconsciousness fun that immediately charms the viewer out of any dialectic frame of mind: it truly is as if a child who’s set on circling to dizzydom has seized the viewer’s gaze. There is no attempt to ‘mystify’ the ‘facts’ or deliberately confound or torture the viewer’s spatial context. ‘Chambers’ generates a welcome ‘footedness’ that does indeed extract a poetry simply in the sharing of already knowns.

The final shot delivers childlike pushing to extremes, a dizzy twirl that sportively regards the ceiling domes, then comes to rest in the dark–this time black leader that signifies the end.”

– Gail Camhi, “The Downtown Review,” 1980

Chinatown (1978, b/w, 16mm, silent, 5 min.)

Not to be confused with “Made in Chinatown”

City Opera (2000, color, 16mm, silent, 6 min.)

“Shot during a stay in San Francisco, Jennings’ film consists of rhythmic flows of color and shape reverberating in this sensual glimpse of a reflected and refracted city.”

Close Quarters (2005, b/w, 16mm, silent, 8 min.)

“It’s possible that I am overvaluing this film, although I don’t think so. Even though I have seen a few Jennings films I haven’t responded to, his mastery over the medium, his orchestration of light and chiaroscuro is unrivaled. Like Miracle on 34th Street and Silvercup, Close Quarters partakes of the physical world as an occasion for abstract light play, but here Jennings is creating relationships between light as pure form and light as a record of living beings, resulting in a new emotional depth that makes this film an artistic breakthrough. This is the film that should be called “fugitive light,” since Jennings draws with the sun that pierces gaps in the curtains, those moments when the line or a slash on the wall will coalesce for a few seconds. But in the midst of this we see his actual apartment, his cats and his lover, and they too are allowed to emerge as pure light. And yet, they retain their identity; they are not reduced to abstract forms. The film is a play between the urge to “escape” the domestic via an aesthetic sensibility, and an undiluted love for the domestic, a gathering of bodies and shadows as co-equal loved ones. This is the film that a certain segment of the avant-garde has been trying to make for nearly fifty years, and the painful, radiant beauty of it — its full embrasure of a sliver of ordinary life, one that shines forth simply because it is so unreservedly loved — brought tears to my eyes. “

Jim Jennings’s Close Quarters (2004), which I saw at TIFF 2005, impressed me to the extent that I now use it as shorthand for the style of filmmaking that discovers transcendent beauty in the everyday. Close Quarters, which was shot entirely within Jennings’s New York home, is a montage of near-abstract images — shadows moving against a wall, light pouring through a curtain, the face of his cat — but his mastery of chiaroscuro never subsumes the “real” subjects of his gaze.

– Darren Hughes, Long Pauses

“(An) experimental kammerspiel comes to mind: Jim Jennings’ chiaroscuro Close Quarters, which uses vertical blinds to sublime and sexy effect; a romantic sort of cabin fever, less cagey, more bedroom tussle.”

“Jim Jennings’ “Close Quarters” (2004), etches scaly textures and carves wedges of light into a silent, velvety shadowbox where a cat stands watch over a sleeping mistress. Jennings teasingly conflates the cat’s paw with the woman’s bare feet protruding from the covers….”

Clothesline (1977, color, 16mm, silent, 5 min.)

Stretched across the sky until the film bursts. – Jim Jennings

Color Blind (1983, color, 16mm, silent, 8 min.)

Framing out recognition to liberate color and form from the subject so that they become the subject. -Jim Jennings

Counterpane (1979, color, 16mm, silent, 5 min.)

Daily Commute (2002, color, 16mm, silent, 8 min.)

A colorful film that depicts weary workers making the trek home from their jobs, as oblivious to the whimsy that surrounds them as they are to Jennings’ camera. In the pre-smartphone era, Jennings managed to film these subway riders behaving naturally, as though they recognized him as a fellow worker (a plumber) or understood he was making sensitive art. This is a film that finds magic in the everyday and makes the most mundane of activities a source of genuine fascination.

– Karen Treanor

Daily Commute features “common” men and women returning home after a long day at work. The rhythm of the subway trains and the motions of the camera suggest the workers’ gentle weariness and celebrate their quite perseverance.

– Karen Treanor

Day Dream (2001, b/w, 16mm, silent, 7 min.)

“In a way, making street films is daydreaming with a camera. It’s capturing a fantasy you’re having when you’re wide awake and life is going on around you. There is, of course, a similarity between daydreaming and making any kind of art because they both spring from that narrow groove between the subconscious and the conscious. That’s when self-expression and technical problem-solving both flow together in an almost mystical way. For me this film represents that mental state. I shot it in late July 2001 but put it away for some forgotten reason. It’s very much about everyday life–a nondescript New York neighborhood on a calm Sunday afternoon, garbage cans piled high, feet reading here and there . . . but it’s also about the magic I can see in that world when I free my subconscious. I made this film so effortlessly (I just cut out one brief shot) because I was so fully in that mindset, which, I think, shows in the nature of the images.”

-Jim Jennings, catalogue of the Filmmakers’ Co-op

Dispatch (1979, b/w, 16mm, silent, 9 min.)

“‘Dispatch,’ another black-and-white film, begins with oscillating greyish surface modulations that move sideways on the screen, rendering our view a partial window to some larger movement taking place. Geographic graphic ribbings then ascend, and as perceived, the thought occurs we might be watching animated film. A shadow of a truck’s front end appears in movement, then comes gently to a halt: we know this image to be photographed, and yet the texture of the film itself hasn’t changed at all. Further readings of the upwards, downwards, and occasional obliquely graphic movements of the patterns on the screen soon describe to us the vantage point of the camera stationed above some traffic intersection.

Once privy to Dispatch’s ‘secret,’ i.e. knowledge of its utterly abstracted image source, one might anticipate diminished sympathy for further images along these lines expected to arise, but this is not the experienced at all. Instead, Dispatch unfolds along several further elevated keys, undeterred by having ‘lost its cool” to what orthodox abstractionists might view as indiscreet confession. Delectable paint drippings, pock-marked metals with variegated zonings on them, corrugated truck tops with some stencilled numbers all conspire to arrive, whiz by, or gently comport their pre-established dwelling places in the frame so that the viewer inadvertently engages in the delicate trompe l’oeils emerging. One suggestive clue to the nature of a moving surface then reveals itself to be, surprisingly, a truck; another, a car. Another surface leaves us with its disappearance a shadow of a tree, and we assume by what has gone before that what just passed was traffic, too, but specifically we’re at a loss to provide it with a name.

The spacings in between ‘events’ and the length of the ‘events’ themselves describe a breathing in breathing out of moments that qualify, not quantify, the anecdotes portrayed. In the short span of this film’s eight minutes we witness trucks and other traffic ‘beasts” in magical procession. A recent-vintage car, in passing downwards on the screen, asks us to look on its comely Detroit body. With a fast bright wink to all concerned, its windshield is reflector of the sun and skyscrapers around, and as a result appears as one impeccably dressed gangster who sports sunglasses, not wishing to be ‘seen.’ Behind him rides another shady character, similarly dressed.

Refreshingly, there is no taxing of the viewer’s nerves to prove a worried point. Alive abstracted surfaces present themselves, then move, then tarry, then sometimes identify their species as the camera apprehends their presences like happy visitors in view.

The last shot of Dispatch provides a longer than previously given dark, which finesses the viewer to be reading further traffic ‘signals,’ to read the surface as abstracted darkish vehicle or closeup of the road, only then to have it dawn on him or her that this is indeed the end.”

– Gail Camhi, The Downtown Review, 1980.

“(In) ‘Dispatch,’ the interaction between what is filmes and what the camera does is…symbiotic. The film is shot from an overpass. The camera with a medium-range telephoto lens is pointing at the vehicles below. As the film starts, a light grey out-of-focus surface moves slowly to the left uncovering the unexpected sharp, grainy surface of asphalt on which there is a shadow of a tree. The grey surface was a truck top whose tail stopped at the left edge of the frame. The static asphalt came as a shock to the unresolved between whether the camera was panning or the grey surface was moving.

This will be a recurring effect in the rhythms that follow. A truck and its trailer top move up the screen; before a cut can be felt, another truck top moves down the screen, strongly suggesting cinematic wipes. The metal patterns on top of the trucks become transformed by their speed into still lines in a stroboscopic effect, or at other times, are just a blur, or slowly moving, hesitant, stationary, or moving backward, in a wild jumble of abrupt and slow changes. The camera, usually static, adds to the tension and ambiguity by occasionally moving. It does so either to subtly change the point of view during the truck top wipes or, at the end of the wipe, as if to awaken from vertiginous thrills. There are numerous jump cuts, complicating and accentuating the tempo of the various movements. Counterpointing these are a number of short shots, often involving very slow movements and sharp shadows. The variety of the vehicle tops is quite impressive including cars and large flat-bed trailers that give the impression that either the space is caving in or that the road itself is moving.

As with the leaves in (Jennings’) ‘Refraction,’ highway trucks and cars move by constantly and can be hypnotizing. The filmmaker with his camera contradicts this experience when he transforms and appropriates the vehicles’ movements by fixing them on film. Jennings’ understanding and appreciation of how car and truck movements could effect (sic) the whole frame and filmic temporality give impetus to the film in a very physical way. Many decisions appear to have been made when filming in a mood of acute filmic awareness and spontaneity. The effect of the film is also physical because of the disorientation of space, the tension in the picture plane, the visual surprises, the rhythms, and because the film is intricately choreographed to value every moment of these filmic experiences. This is rare and refreshing. Like Eisenberg, Miller and Gidal, Jennings in their various ways, Jennings is forcing a medium, so often stuck in an exclusive usage as a sign language, to vibrantly acknowledge its more fundamental intuitive and physical aspects.”

– Vincent Grenier

Dwellings (1997, b/w, 16mm, silent,24 fps, 7 min.)

“Dwellings” proposes that all houses in which men and women have lived are haunted. Spirits continue to linger in them, in the borders between light and shadow.

– Karen Treanor

Edge (1972, color, 16mm, silent, 6 min.)

When Jim Jennings was a student at Bard College, his professor, Ernie Gehr asked the students in his class to form a frame with their hands, by joining thumbs to forefingers. They were told to walk around “framing” scenes in that manner. Jennings was struck by the simplicity and effectiveness of the lesson and produced this film as a result.

– Karen Treanor

Elements (2002, b/w,16mm, silent, 7 min.)

Elements refers not only to the natural elements, which are variable and even capricious, but also to the social elements, working-class people who are trying to maintain order and routine.

– Karen Treanor. NYFF “Views from the Avant Garde”

Eyedrops of pearl-grey rain bead along the surfaces of Gotham City. Peripatetic man “on the beat” Jennings plays raincatcher, capturing the moments of parenthetical reflection brought on by weather and its softening force of delay. He finds, in the small details of off-handed moments under close observation, elective affinities – a casual pageant of relative inactivity, and the specialties of ordinary goings-on muted by precipitation.

Elements is an ode to fortuitous inclemency. With his eye for formal abstraction in near perfect balance with drifting documentation Jennings perseveres, in a city nearly photographed to death, in bringing to light familiar elements saved from disregard and savored into sharp filmic articulation.

“…’Elements’, where Manhattan cityscapes are viewed through the physical and emotional blurring of a rainstorm.”-Press release, River-to-River festival, NYC.

The Elevated (b/w, 16 mm, silent, 12 min.)

“The Elevated” captures the ethereal beauty of a structure that is usually considered solely functional. The film considers the lace-like geometry of the elevated, Queensborough Plaza subway station, as well as the varying motions of its trains.

– Karen Treanor, Notes to Jennings’ MoMA Cineprobe, February 23, 1998

Escape (1994, b/w, 16mm, 24 fps, silent,7 min.)

In “Escape,” Jennings does NOT focus on the shifting scenes outside a train window, but rather on the utility wires that line the route. By doing so, he creates an hypnotic, spiritual experience that provides both the comfort of the constant and the excitement of minor change.

– Karen Treanor

F Stops (1999, color, 16mm, silent, 7 min.)

Colors swirl in this playful film, shot along the “F” subway line in New York. Obviously, the title makes reference to both the train line and to film exposure.

– Karen Treanor

Fashion Avenue ( b/w, 16mm, silent, 7 min.)

“Filmed in New York’s Garment District, Fashion Avenue uses mirrors to reflect something more beautiful than the world of glamour: The everyday lives of working people. The filming of reflections creates the effect of printed fabrics, and the often jagged shapes resemble sleeves and lapels on the cutting-room table.”

– Karen Treanor, Media City catalogue

“Jim Jennings’s silent cinematic poem reflects a kind of “mirrored life”: filming in New York’s Garment District, a centre for fashion design, he focused on reflecting surfaces – display cases, windows – and captured richly nuanced black and white shadow plays and distorted images reminiscent of those found in a hall of mirrors. Some fantastic figures emerge in the reflection of cut glass, while people passing by and objects drifting in the wind act as shadowy figures from a foreign land beyond glamour.”

– Viennale catalogue 2017, Viennale ‘09

Garbo Talks (Late 1970s, early 1980s, 16mm, found footage, b/w, sound, 2-minute loop)

In this newly re-discovered film, Jennings uses found footage of actress Greta Garbo in Grand Central Station, returning from a trip abroad, surrounded by photographers. As flashbulbs flare, Garbo hides underneath a large-brimmed hat as she walks out of the station onto the street and into a car. (Anecdote: In 1991, shortly after Garbo’s death, her niece, Gray Reisfield, inherited her exuberant apartment in the Campanile Building in Sutton Place. Reisfield hired Jennings’ plumbing company to renovate the bathrooms. Upon receiving the bill for the plumbing work, Reisfield exclaimed, “My husband’s a doctor and he doesn’t make this kind of money!” Jennings couldn’t resist keeping the handles to Garbo’s shower and installed them in his own home.)

– Karen Treanor

Gardening Secrets (b/w, 16mm, silent)

From the first frame, this film is a surprise. A garden film in black-and-white? Where are the crimson roses and sunny yellow dahlias? In this film, the flowers are merely a backdrop for the drama created by a stealthy squirrel, an impassive pigeon, assorted insects, and the shadows that fall across a Buddha sculpture, as well as the hoses, buckets and shovels that suggest an unknown (human) gardener. Like filmmaking, gardening requires light and labor, tools and skills, imagination and sensitivity. Although this is a completed film, Jennings has never screened it publicly because he deems it a “minor” work.

– Karen Treanor

Go fly a kite (1980)

This film was lost for many years, until it was re-discovered by preservationist Genevieve Havemeyer-King in 2017. It was screened at the Collective for Living Cinema on White Street in 1980. The show also included slides by Jim Jennings and John Matturri, along with live music by John Zorn.

Greenpoint (2007, color,16mm, silent, 7 min.)

“Jim Jennings’ “Greenpoint” is a rapturous and observant portrait of Greenpoint, Brooklyn, that pays tribute to a working-class neighborhood on the verge of gentrification. It is a jazz, boogie-woogie collage of hot colors, peeling posters, graffiti art and neon signs.”– Karen Treanor

Instead of being a “city symphony,” Greenpoint is a neighborhood jam session. In lieu of skyscrapers and Civil War monuments, we see Mom-and-Pop shops and the detritus of daily life. This film is a frank and loving portrait of a Brooklyn neighborhood. -Karen Treanor

Hall of Mirrors

See “Fashion Avenue”

Impossible Love (2001, b/w and color, 16mm, silent, 10 min.)

The title Impossible Love suggests the miraculous amidst ever-present doom and beauty. Shot in Venice, Italy, the film was edited in the camera except the first B & W section. In this work, “illusion” overpowers “reality” and then ends abruptly, tragically, romantically.

– Karen Treanor, New York Film Festival, “Views from the Avant Garde,” 2001

Interior (2001, b/w,16mm, silent, 8 1/2 min.)

Shot in a Queens, New York apartment, Interior depicts rooms as emotional states of being. The apartment represents the comfort and torment of domestic life. Like a human skull, it holds images that are imbued with associations both painful and sublime.

– Karen Treanor, New York Film Festival, “Views from the Avant Garde,” 2001

Intrigue (1998, color, 16mm, silent, 14 min.)

Surrounded by strangers under the El in Brighton, Brooklyn I submerge myself through the lens of the camera into a childlike world of colors separated from objects, floating to the surface and escaping, as day turns to night and estrangement gives way to emptiness.

– Jim Jennings, quoted in the catalogue of the 43rd San Francisco International Film Festival

Jackson Heights (2010, color, 16mm, silent, 14’22 min.)

“Jackson Heights” was filmed in a Queens, New York, neighborhood, fondly called “Jai Kissan Heights” (“Long Live Krishna Heights”) by its predominantly Indian residents. The silence of the film seems ironic in that much of “Jackson Heights” was filmed in an area named “Speaker’s Corner,” where members of the public voice their religious and political opinions as they hand out leaflets to passersby.

– Karen Treanor

– Viennale catalogue 2017, Viennale ‘09

Leaves (1975, color, 16mm, silent, 8 min.)

“‘Leaves’ by Jim Jennings takes close shots of trees, leaves dominating the foreground. Wind and light are again central themes of attention. But there is more. Through the leaves we can see park benches and cars. We can use the background detail to figure out the angles of each shot. At one point there is an irregular yellow splotch amidst the leaves. Is it autumn? Suddenly, the splotch moves. It was a cab waiting at a traffic light. A variety of detail inhabits Jennings’ simple format. Foreground is played off background. It creates tension, a quality woefully lacking in too many films.”

– Noel Carroll, Soho Weekly News, quoted in flyer for the San Francisco Cinemateque, 1977

In “Leaves,” Jim Jennings moves the tree from the periphery of urban life to the center. It’s leaves form a green “curtain” through which we view the activities of the City’s denizens.

– Karen Treanor

Lost and Found (1983/2013,b/w, 16mm, silent, 5 min.)

Jennings shot the original footage (of a ride on the Staten Island Ferry) in 1983 and rediscovered it in 2013, when it was screened at the New York Film Festival’s “Views from the Avant Garde.” As is typical of Jennings’ work, the film mines every aesthetic possibility in a quotidian situation. In this case his eyes are drawn to the motion of the boat in relation to the scenery outside its windows, to the characters of individuals and their relationships to one another and the sheer, visual and emotional (Dare I say “spiritual”?) beauty of it all. The passengers, on their daily commute, remain unaware of the splendor Jennings sees–and makes us see.

– Karen Treanor

Lost Our Lease (2013,b/w, 16mm, silent, 10 min.)

“Lost our Lease” was filmed during working hours going from here to there in and out of a work van playing hooky. It was shot and edited around 10 years ago and the title was given to me from the street.”

– Jim Jennings, catalogue of New York Film Festival’s “Views from the Avant Garde“.

“When this film was screened at the New York Film Festival, Jennings expressed the desire to continue to shoot films in New York City “until the last of the sweatshops is turned into a luxury apartment.” This film captures the “sign” of our times, the “Lost Our Lease” sign in the window of a humble storefront. We become aware of the beauty of the vulnerable, remaining patches of gritty New York. Nevertheless, the film is not “about” gentrification or materialism or any such matters. It exceeds the limits of social commentary and ventures into a realm timeless and exquisite.

– Karen Treanor

Made in Chinatown (2006, color, 16mm, silent, 8 min.)

“I met Jim with Henry (Hills) and Vincent (Grenier) and Ken (Jacobs) in 1980 when I returned to NYC from SF. Always intrigued with his work, remembering seeing an early ‘minibike’ film at Henry’s place on 8th street, and another work of great beauty: silhouettes of bodies down on Wall Street. High modernism with an intimate feel.

Later, in the early oughts, seeing work at the New York Film Festival when Mark McEllhatten was programming Jim regularly, made me sit up and take notice, once again. The film I remember was unusually for Jim, in color —of Chinatown in the snow. Beautiful, ephemeral light. I invited Jim up to school that fall as a guest artist at the SMFA, The School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, where I taught. I knew the students would love this work: the Bolex, daylight–—all the tools they were using and here, exquisitely handled. I learned then that Jim, instead of exposing for the shadows, as the Hollywood pros would, was exposing for the sunlight. Letting the blacks go deep and dark. Finding on the street the fugitive faces and moments that the rest of us might notice but had never captured in the quick darting tender embrace of Jim’s celluloid. That he, as a plumber, sitting on the Avenues, waiting by his truck, lunch or a break, would find the time, the inclination, the poetry of the street, the Whitmanesque masses central to his project. Faces: anonymous but familiar, heroic in their dailiness and dignity. Kind of like Jim himself.”

– Nathaniel Dorsky, notes for “Jim Jennings & Friends, February 11, 2017, Anthology Film Archives.

“Jennings, a prolific and consistently wonderful filmmaker, excels at constructing near-perfect short films out of glimpses of fleeting, ephemeral visual phenomena. Made in Chinatown is a street film in which the human presence is represented only indirectly and in fragments, either through its reflection in shop windows, cars, and other surfaces, or through the shadows it casts. There is nothing extraneous here, nothing which upsets the film’s fragile, delicate balance between what is physically substantial and the immaterial traces of that substantiality.”–“Senses of Cinema,” October 1-2, 2005, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia

Megalopolis (2000, b/w, 16mm, silent, 6 min.)

A high contrast, black-and-white architectural study of Manhattan skyscrapers, Megalopolis is a symphony of shapes and forms. Slivers of light and masses of darkness sweep across the screen in this wonderful, graphic work.

– Susan Oxtoby, Vienna International Film Festival 2003

Minibike Ride, see “The Minibike Ride”

Miracle on 34th Street

Normally one thinks at Christmas of a time of colors, light and faith. In Miracle on 34th Street, however, Jim Jennings presents the holiday as a period of gloom, shadows and commercialization. The film was recorded in front of Toys ‘R’ Us in Herald Square in the weeks before the turn of the Millennium. It shows shoppers leaving the store laden with packages. The mood of the film suggests that the consumers are about to be “consumed” – by the spirits of materialism that flit through the streets. The bags the buyers carry cannot contain the only gift that is worthwhile: Love.

– Karen Treanor, Vienna International Film Festival 2000

“Shot at the close of the Twentieth Century (symbolized by the closing door, repeated twice at the end of the film), this work expresses human frailty within an abstract play of black-and-white miraculously fluctuating between two-dimensional and three-dimensional pictorial space as individual definition is lost in common mortality.”

– Anthology Film Archives catalogue, July-August-September 2001

Nocturne

“Filmed in Haarlem, The Netherlands, ‘Nocturne’ captures the exquisite fragility of human endeavor. Human inventions–street lights, car headlights and canals–perform an elegant ballet. While designed for utilitarian purposes, they become elements of a delicate and mysterious beauty.”

– Millennium Film Workshop announcement for solo show, November 23, 2001

Nuke Brink (1980)

Starting in the 1980s through to the late 1990s, Jim Jennings abandoned his own filmmaking to serve as Cinematographer, Technician, Editor and Actor for his then-wife, Artist Christine Piazza. (He also served as the Assistant for her sculpture work.) “Nuke Brink,” which Piazza wrote, directed and stars in, is a silent, Jack-Smith-inspired film that parodies cinema classics, such as Erich Von Stroheim’s “Greed” and Mike Nichols’ “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” The title refers to the Three Mile Island nuclear accident, which occurred just prior to filming.

– Karen Treanor

Painting the Town (1998, b/w, 16mm, silent, 10 min.)

Last autumn on a series of weekend nights I went to “The Crossroads of the World” with a camera and a tape recording of an Opera I love. I played the Opera and shot film for hours at a time. Later in the editing room, I removed what merely documented and braided the sublime.

– Jim Jennings, quoted in the catalogue of the 43rd San Francisco International Film Festival

“As a teenager, I started making films in the late 60’s with a 16mm Keystone camera that my father’s family had used to make home movies in the 30’s, 40’s and 50’s. Since graduating from Bard College in 1973 as a Film Major, I have lived in NYC, making films on and off, while simultaneously being employed in unrelated fields. On more than one occasion I tried and failed to make a film in Times Square. A year ago while walking through there at night, I was inspired to try again. The filming was done on consecutive weekend nights. Between weekends I would have the 100-foot roll or two developed and project them once or twice. Propelled by “chords” and “melodies” that tantalized me, I would then go back for more in the editing room, after exhausting the shooting process, I freed my “Lullaby of Broadway”. On the two occasions I’ve screened PAINTING THE TOWN, I dedicated them to Ken Jacobs, whose work and encouragement I am grateful for.”

– Jim Jennings, catalogue of the Filmmakers’ Co-op

Poems of Rome (1997, color,16mm, silent, 7 min.)

I jumped a tram in Rome and rode it to the end of the line. On the way, a shadow on a wall caught my eye. The next morning I went back to the shadow on the wall and made this film.

– Jim Jennings, quoted in the catalogue of the 43rd San Francisco International Film Festival

“The first film in the trilogy, which was filmed at a train station in a quiet part of Rome, suggests a harmony between ‘rootedness’ and ‘mobility,’ as well as tradition and innovation.

In the second film in the series, Jim Jennings uses an array of powerful visual symbols to address relationships between human desires and eternal forces. This film reveals connections among ‘The Will to Power,’ the need to create and the nature of ideals.

Filmed near a Roman train station, the third film juxtaposes the technologies, resources and aesthetics of ancient and modern societies, using the metaphor of a single day.”

– Karen Treanor, Millennium Film Workshop catalogue, Fall Series 1998

Prague Winter (2006, b/w, 16mm, silent, 8 min.)

Jennings is best known for his portraits of New York City street life, and with good reason; his patient eye and deft camera-stylo approach represent one of the key contributions to the “city symphony” genre since its heyday in the 1940s. Jennings, along with Ernie Gehr and Ken Jacobs, is one of the preeminent urban film-poets. He does regularly stray beyond this mien, sometimes exploring the domestic interior (as in his 2004 masterpiece Close Quarters) but also packing up the Bolex and filming urban doings abroad….So part of what’s so surprising about Prague Winter is that it feels so lived in, so thoroughly grounded. It’s not so much that Jennings makes Prague look like Manhattan (although there are commonalities in terms of architecture and the gaps of light between it). But the film restricts itself to sights on and around the tram, which provides an uncharacteristic linearity to the film. What’s more, Jennings’ status as a guest observer seems to bring out a humanism in his work, as he fixates on the elderly and, implicitly, the history to which they’ve been subjected. The post-Communist malaise hardens into grim acceptance, and this, along with the physical traces of Prague’s history as manifested in the built environment, is what fascinates Jennings here. His camera is tender and unobtrusive, as you would expect from a filmmaker of his sensitivity.

– Michael Sicinski, “The Academic Hack”

“In this essential visualist’s work, the comings and goings of the city, its street cars, and its people are seen through the lens of a noted filmmaker of the avant-garde. Unassuming yet haunting, black and white cinematography reveal a candid portrait of the Czech Republic’s Capital.

Prague’s checkered history seems to resonate as the filmmaker rides, among other conveyances, the rails of the tram system, which includes the Nostalgic Tram no. 91.”

– 27th Annual Black Maria Film & Video Festival

“Jennings’ ‘Prague Winter’ has its own formal dynamics but offers up a solemn and compassionate view of physiognomy and fate, exploring a city speckled with snowfall and populated with elderly hibernal figures moving along their well-worn paths.”

– Mark McElhatten, notes from The New York Film Festivals’ “Views from the Avant Garde,” 2007

Proximity (1973, color, 16mm, silent, 4 min.)

Public Domain (2007, color, 16mm, color, silent, 9 min.)

“As a critic, there aren’t that many films I feel confident recommending sight-unseen. In the case of this year’s Wavelengths series, where not everything was available for preview, there are three films I do feel utterly confident in directing any reader toward, simply because they’re made by three of the finest avant-garde filmmakers currently working anywhere in the world : Ernie Gehr, David Gatten, and Jim Jennings. A few years ago, Jennings’s film Close Quarters was featured in Wavelengths, and while I was already a Jennings fan, that film did more than just blow me away. It reduced me to tears, and by the time all was said and done, I realized that Close Quarters was a flat-out masterpiece. (For those who care, I typically employ a 1-10 rating scale, and have awarded only around twelve 10s since I began. Quarters was one.) Last year, Jennings returned to TIFF with another fantastic film, Public Domain, a fast-and-dirty NYC city symphony that effortlessly encapsulated a hundred-plus years’ worth of cinematic ways of looking at a metropolis. Jennings is, by my lights, a modern master, almost always composing his films at the editing table like some visual equivalent to musique concrete, his films’ silence leaping off the screen like sculptural Free Jazz. Neither meditative nor overbearing, Jennings’s films dart across the screen as a sort of bike messenger of the senses, giving your brains a run for their money. His new film is Greenpoint, and I am counting the days until I get to see it. “

– Michael Sicinski, MUBI

“Public Domain, made in response to an ill-conceived and since-rescinded edict involving heavy taxes for filming in New York City, is both a classic on-the-fly, man-in-the-crowd city film, and an implicit hurrah in favor of the unauthorized camera-stylo liberty that has defined the avant-garde. Jennings’s edits turn people, buildings, windows and shadows into tectonic ballerinas in a volumetric dance, and the results are electrifying and joyous. This is one film you’ll regret being able to see only once.”

According to program notes, Jennings made Public Domain in response to Michael Bloomberg’s (failed) initiative to levy prohibitive costs on those seeking to film in New York City. In a sense, Jennings’ film is an ideal demonstration both of what would be lost if NYC imagery were restricted, and, perhaps more importantly, of how any such law would be meaningless, since a world of fleeting fugitive images exists beneath the radar, well below the ken of even the most intrepid “independent” filmmakers whose aspirations chain them to 35mm film crews. Jennings, as a one-man band and total mobile unit, can move undetected through the bustle of the streets and collect fragments of life that the Woody Allens and Spike Lees of the world wouldn’t notice. Now, having laid out what I take to be the thematic justification for the shape and form of Public Domain, let me say that no precis can express the sheer exhilaration, the formal precision and nonstop observational inventiveness of the film itself (I’m not sure if such a concept — observational inventiveness — isn’t an oxymoron. But Jennings attunes himself to what’s around him, and achieves such varied results in the process, that I sense he continually finds new ways to observe the spaces he moves through, a sort of active passivity.) Jennings has been one of the un(der)sung heroes of experimental cinema for decades now; his body of work clearly shows him to be equal in stature to acknowledged masters such as Ernie Gehr, Ken Jacobs, Nathaniel Dorsky, and Warren Sonbert.

There are highly compact formal micro-dramas that characterize Public Domain‘s overall montage logic, in which brief quotidian gestures are glanced, then shown either on their side or right side up, so as to emphasize both the pure movement and rhythm within the frame and its human / geographical content. That is, when we see the distortion of buildings as reflected in the side of a moving bus, Jennings presents it twice or in some cases three times, with different orientations, so that we can quickly apprehend the formal information while the subject matter retains its denotative connection to the life of the city. What’s more, within this overall bustle (less city symphony than string quartet, a set of sharply articulated scherzo maneuvers) Jennings even seems to expand on the theme of the “public domain” of the unrestricted cinematic image, with moments that recall other great avant-garde films and filmmakers, an entire tradition that didn’t wait around for permits. We see Dorsky’s floating bag, the wobbly buildings of Manhatta and N.Y.,N.Y., the upended pedestrians of Gehr and the urban grunge of Jacobs and Jack Smith. Jagged moments in the editing, shuttling us from the pavement to the sky, strike me as Warren Sonbert moments. And yet, in terms of color, lighting, tone, and pacing, everything is of a piece, and unmistakably organized by Jennings’ unique sensibility, one which eschews detachment in favor of complete beatitude in the face of urban chaos. Public Domain, like all of Jennings’ New York films, are records of the pleasure in being bumped into when you stop to think. Far from marking the cessation of thinking, that jolt simply occasions another, newer thought.

– Michael Sicinski, “The Academic Hack”

“…Jim Jennings’ Public Domain is done in startling, plastic color, as the filmmaker grabs snatches of imagery from below mid-town in Manhattan. Not having seen any work by the filmmaker before, it was difficult, in the montage flurry, to grasp at what I was supposed to be seeing beyond the rhythm and the color. But soon, falling into the film’s incredibly brisk movement, I began to be thrilled by Jennings capturing the barest minimum of gestures and signs. Not a series of gestures, mind you, but seemingly the movements, the meaning, the text grasped at a split second in the dead center of its being, the beginning and end of each ‘thing’ neatly, economically cut off, leaving at once a suggestion and something pure, centered, and instantaneous: the most whole of things caught for the briefest of moments, both so small and so fast it is nearly impossible to say what they were.”

Refraction (1972, color, 16mm, silent, 4 min.)

“In “Refraction,’ the camera is set so that the leaves of a large tree fill the frame. Green ordinary leaves which move in their baroque ways under the wind. In a sense it is shocking to put on film such ordinary things, things which could be so easy to dismiss. Yet this undemanding, pleasant image hides something. The image IS of what one hypnotically stares at in forgotten moments, amd from which one wakes, when shapes make themselves up in it. These furtive possibilities confront the delimiting, all-eyes-cinema. The intimate sensation is made to bear on the public circumstances of film, provoking new readings of the moving leaves. As the image presses its quiet offerings on the viewer, a subtle interaction occurs between changes of speed in the camera and wind as they, in different ways, accentuate or diminish the speed of the fluttering leaves. Both the changes in camera speed and the changes in wind affect the illumination and modulate the created rhythms. The variations, fleeting and startling, expose the hypnotic and liner states of mind, to leave us in a condition which is unsettled but palpable and moving. “Refraction’ is a humble film that succeeds in uncovering the contradicting but unexpected profundity of small things.”

– Vincent Grenier

San Cristobal (1983/2011, color, 16mm, silent, 6 min.)

“San Cristobal” explores the interpersonal tensions between Native Americans and Caucasian tourists in the Mexican highlands. With deft camerawork, a keen sense of composition and color, and emotional sensitivity, Jennings’ acknowledges the material poverty of the Mayan peoples, while celebrating their vibrant cultures.

– Karen Treanor

Jennings plays with dimensionality in this film, which was shot in San Cristobal, Mexico. The film opens with deep shadows cast by the Chiapas sun. As the marketplace fills with people, the film is transformed into a flat plane of colors–vivid greens, hot pinks, bold turquoise, blazing reds….Within this flat plane, the viewer can discern representational forms–a woman’s glossy braid, a straw basket, a humble sandal, a child’s face….This is a beautiful, loving film.

-Karen Treanor

School of Athens (1997, b/w, 16mm, silent, 14 min.)

“…we enter the absolute monumental. Raphael’s wildly passionate painting has shaken Jennings to the core. Fiercely sexual, tumultuous, his filming of the painting rages on without thought of onlookers; cadenced timing and concerns with proportions out of the question. The film is monstrous, reckless and I couldn’t admire it more.”

– Ken Jacobs, quoted in the catalogue of the 43rd San Francisco International Film Festival

“Jim Jennings’s The School of Athens (1997)…shows how a silent, near-abstract film can create considerable tension: in this black-and-white filming of a Raphael painting, Jennings intercuts different perspectives, often from oblique angles, to create visual dramas out of small changes in camera position.”

– Fred Camper, The Chicago Reader, “People Issue 2016”

“Based on a photograph of Raphael’s painting, ‘The School of Athens’ offers a view of passions–earthly and unearthly, physical, emotional and intellectual. The process of ‘re-photography’ enables Jim Jennings to reconfigure an early 16th-Century masterwork, and to transform its images into fresh, personal expressions of intense feeling.”

– Karen Treanor, Millennium Film Workshop calendar, Fall Series 1998

Shades (1985, b/w, 16mm, silent, 7 min.)

“Unfolding buildings drawn across the screen in spectrums of grey reflecting buildings in their surfaces cutting the sky into triangles.” -Jim Jennings

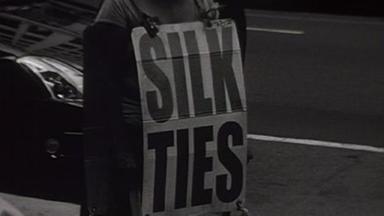

Silk Ties (2006, b/w, 16mm, silent, 7 min.)

“Jennings’ latest is a dense chiaroscuro NYC citysong, although rhythmically Silk Ties finds the filmmaker mining new possibilities. Whereas Miracle on 34th Street and Painting the Town are true camera-stylo films, using the gestural qualities of handheld 16mm with utmost grace and fluidity, Silk Ties uses staccato (in-camera?) editing to lend his images a jaggedness that (as Lee Walker mentioned afterward) recalls abstract animation. Street scenes, thick and dark and shot with the f-stop way down low, alternate with shots of skyscrapers and the negative-space sky between them. The jumps in editing seem to make the buildings dance, and create little jumps in the life of the streets, strangely enough lending this activity a kind of stately poise rather than heightening its implicit kinetics. But in addition to the paradoxes of stillness and movement, Jennings constructs a kind of disjuncture between past and present. Certain aspects of Silk Ties, especially the architectural compositions, recall the classic city-symphonies of the 1920s and 30s, especially Manhatta. Furthermore, the exaggerated darkness of much of the film gives it a distant quality, like something excavated from another time and place. But Jennings’ image selection forces the viewer’s consciousness back into the present. A perfectly “timeless” New York scene is sent forward to the present by, say, a Taco Bell Express sign, or (more pointedly) the predominance of African-Americans in the film. The cultural makeup of New York is much different than it was 70 or 80 years ago, but Silk Ties‘ representational approach lends today’s Manhattan the historical inevitability, and the grandeur, we associate with images of earlier times. In short, Jennings has made a film that can be regarded as a document of who and how we were, right now. “

– Michael Sicinski, “The Academic Hack”

“…among the best shorts I saw in 2006. A city symphony in miniature, Silk Ties is never short of stunning to look at. Like so many great photographs, the stark black-and-white images here seem to have been stolen from some slightly more magical reality. (After seeing the Jennings film and Nathanial Dorsky’s Song and Solitude on the same program, I walked away wishing I could recalibrate my view of the world around me, which, I guess, is one of the more noble functions of a-g cinema.).”

– Darren Hughes, Long Pauses

“Jennings mostly shot ‘Silk Ties’ in New York’s Garment District from the vantage point of a work truck. Filmed while parked on the street and driving in traffic, Jennings captures the rhythms and sensation of this vibrant street life. Edited mostly in-camera, ‘Silk Ties’ reflects the working-class sensibility of its environment.”

– Catalogue of the 45th Ann Arbor Film Festival

“…the stunning Silk Ties, where a symphony of stark black-and-white images from New York’s Garment District seem to have been stolen from some slightly more magical reality.” -Press release of the River-to-River Festival, NYC

Silvercup (1998, b/w, 16mm, b/w, 12 min.)

“…its jewel-like magnificence pretty much slapped me upside the head. Essentially a series of high-contrast black and white shots of bridges, trellises, and commuter trains against a blank NYC sky, Silvercup manages to impress with its effortless interlocking shots. If you graphed them out or analyzed them, there would be no concrete reason why, from shot to shot, each framing and camera angle seems to be the logical complement to the last. The film isn’t overbearing, like an Eisenstein montage, nor does it follow any predictable film grammar. But the editing works, like a perfectly curated series of photographs unwinding in time, all modern yet displaying a picturesque urban decay, an unlikely collusion between Franz Kline expressionism and Rodchenko-like Constructivism. Yes, it is perfect. And as we know, perfection is not an accident.”

– Michael Sicinski, “The Academic Hack”

“The first time I remember going to Long Island City was in 1973 to take a hack license exam. What I remember of the bridge and fringes of subway lines above me was oppression. About twenty years later I found myself back there thrilled by the compositions I was making with a still camera and eventually made The Elevated with some of the photographs I took. Often last Winter and Spring I again went back there and ended up expressing a tenderness I felt by making this film.”

– Jim Jennings, quoted in the catalogue of the 43rd San Francisco International Film Festival

“Jim Jennings’ contemplative Silvercup finds soul in the steel bridges and railways binding Manhattan to Queens and a totemic union of past and present in a once-abandoned Long Island City landmark.”

– Todd Hitchcock, “Pleasures of Urban Decay,” Washington City Paper, Aug 9, 2002

In “Silvercup,” trains move along their tracks continuously, as day becomes night and rain falls and ceases. The constancy of the mechanical complements the mutability of the natural. In this film, train, rain, moon and man respond to one another tenderly.

– Karen Treanor

Skyscraper (2001, b/w, 16mm, silent, 5 min.)

Snow Ride (1970-1972, color, Super 8mm, silent, 3.5 min.)

A sled ride is captured on a sunny day.

South of the Border (1983/2011, color, Super-8 transferred to 16mm, color, silent, 9 min.)

“Footage shot on Super 8 in Mexico in 1983. It sat in a box in a closet for 5 years or so. I came across the footage in the 90s, had it blown up to 16mm, spent a lot of time editing it, and came up with this in the end.”

– Jim Jennings, Media City 2013 catalogue, p. 49

The Minibike Ride (1969, b/w, 16mm, sound)

“The Minibike Ride” is Jim Jennings’ oldest extant film, shot when he was a student at Oakwood Friends’ School. For years, it was shown at Danbury (CT) High School, until the print of it disappeared.

– Karen Treanor

Train of Thought (2009, b/w, 16mm, silent, 7 min.)

“Migrants in the silver rush. Elevated, riding the rails, caught by a sympathetic but prohibited camera, thrown together, bouncing from borough to borough, taking the curves.”

– MUBI

“The film flips subway rushes in various directions and quick cuts to provide a whole line study of Broadway (Queens) boogie-woogie that only occasionally syncopates into rhythms, while giving the wet apparitions of the metro-graffiti, rust, people’s crowded fleeting faces….”

Waiting for St. Gerard (1983, b/w, 16mm, silent, 8 min.)

“Waiting for St. Gerard” tenderly documents the simple piety of the Italian-American parishioners of St. Lucy’s Church in Newark, New Jersey. The men and women in the film patiently await the start of the annual festival devoted to their patron saint, much as they delay gratification on Earth.

– Karen Treanor

Wall Street (also known as “Fall,” 1980, b/w, 16mm, silent, 6 min.)

Shot at high noon in New York’s financial district, Wallstreet is much like a vertical tickertape, charting the existence of typical office workers. The film’s elongated shadows suggest these workers’ depersonalized, neuter, nearly uniform lives, which flow by without any solid or stable element that might provide definition.

-Karen Treanor, quoted in MoMA Cineprobe notes, 1998, and in the catalogue of the 43rd San Francisco International Film Festival

“I met Jim when I first decided to move to New York in 1978 & was seeking out my peers. I myself was obsessed with editing and my initial feeling was that Jim’s films were just camera rolls. WALL STREET was the first film of his which made a strong impression on me, and it is still among my favorites. It was originally called FALL (which I thought was a more appropriate title, as it is clearly shot on a late Autumn afternoon when the rays of the sun cast a noticeably long shadow, and it itself casts a continuously falling motion onto the screen. At the time of the title change I recall Jim told me it was shot on Lower Broadway, but the image reminded him of a wall, and he liked the pun). I took this film to Europe in the early 80s on a program I curated which, as I recall, also included films by Nick Dorsky (ARIEL), Vincent Grenier (INTERIOR INTERIEURS), Caroline Avery (MIDWEEKEND), Abby Child (ORNAMENTALS) and me (NORTH BEACH), and was screened in Madrid & Barcelona, and in Würzberg, Germany. The dazzling, contrasty black & white image of a sidewalk is shot from a moving vehicle (Karen tell me it was a bus, which explains a lot) with a camera rotated 90 degrees; the same several locations appear to be repeated several times. Images close to the camera (like large concrete planters or a pedestrian waiting at a crosswalk) move faster because of their position relative to the lens and are almost entirely black, creating wild abstract moments in the on-going flow of lengthy shadows and the legs that cast them (which themselves sometimes give the illusion of walking backwards). A very clever but relatively simple procedure creates a continuously fascinating progression. Perhaps the shots are just strung together, but somehow the editing strategy seems perfect. In a way it oddly calls to mind Joan Jonas’ classic video VERTICAL ROLL, but it also, and more importantly, seems to create an illusion of a film strip (perhaps as viewed on rewinds).

When I brought Jim to Prague my students at FAMU loved that he was a plumber, rather than a college professor like almost all my other filmmaker guests. It gave them a sense of real authenticity. Several years ago a couple of Jim’s films were on a group program in the Viennale and the authenticity and sheer beauty of his work blew the other pieces on the show off the screen. His work really stands the test of time. “

– Henry Hills, notes for “Jim Jennings & Friends,” February 11, 2017, Anthology Film Archives.

Wash (1999, color, 16mm, silent, 7 min.)

“Jim went to visit some acquaintances, Nancy Campbell and Peter Codella, in Vinalhaven, Maine. They had a question about plumbing, as I recall. At some point, Jim noticed a clothesline with shirts billowing in the wind and shot this film. He didn’t do the plumbing. He just filmed the wash.”– Karen Treanor

Watch the Closing Doors (2012, video, color, sound, 12 min.)

“Well-recognized for his city symphonies, Jim Jennings moves underground with Watch the Closing Doors, a short video work made on a flip camera. Jennings films other passengers during a single journey on the New York City subway, focusing his attention on the commuters’ faces as they wait out their travel and the encroaching platforms as the train approaches its various stops. Synchronized sound captures the conductor’s voice as he offers near incomprehensible advice, including the oft repeated phrase “Stand clear of the closing doors.” Jennings’ empathy for his subjects derives from his own identification, as he is merely one of the many commuters who are experiencing this journey. The public space is transmuted into a private fixation, as Jennings clearly takes pleasure in spontaneously and surreptitiously utilizing this flip camera to capture his journey; but while this experiment may very well have remained private, by structuring the captured footage into a film Jennings makes the journey public once again. Most striking about the piece, however, is the sense of community Jennings implicitly creates: it is often easy to forget that the individual act of getting from point A to point B becomes a communal one through the use of public transportation. Watch the Closing Doors emphasizes the inescapably collective nature of our interactions in the public sphere, and exposes our false sense of individual privacy.”

– Andrea Whyte, Cinema Scope Online, TIFF 2012

Jim Jennings’ first (spectral) video work Watch the Closing Doors — a continuation, yet striking variant upon the filmmaker’s unique city symphonies, this time with synch sound — partakes in the august photographic tradition of capturing commuters unaware on the New York subway.